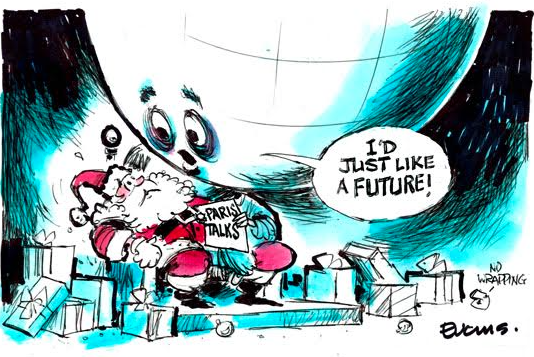

The apparent success of COP21 is dubious to say the least. Its limitations come as no surprise to climate activists who, beneath the self-congratulation of state officials and corporate media, have stressed the enormous shortcomings of the agreement.

To coincide with the closure of another UN-sponsored climate summit, Climate Justice Aotearoa has today launched the Beautiful Solutions Aotearoa project, designed to map out popular solutions to the climate crisis that exist, and as they emerge, across New Zealand. Sam Oldham discusses the impetus for the project.

December 14, 2015

December 14, 2015

The apparent success of COP21 is dubious to say the least. Its limitations come as no surprise to climate activists who, beneath the self-congratulation of state officials and corporate media, have stressed the enormous shortcomings of the agreement. Like previous COPs, it was directly sponsored by a raft of multinational super-corporations, including Coca Cola, Nissan-Renault, among others of the world’s worst polluters. Governments that were party to the summit have always given special representation to these same interests. A glance at the domestic environmental policies of most governments involved in COP21 points to the hypocrisy of their rhetoric there. It is little wonder that UN climate summits have produced the same result for over two decades: business as usual.

The twenty one-year impasse that has been the UN climate summit process points also to the chasm that exists between elite decision-making and popular opinion on the issue of climate change. Globally, ordinary people demand urgent and serious action to curtail global warming. Recent polling of Americans reveals that over two thirds want their government to join a legally binding agreement to reduce carbon emissions, a prospect that the Obama administration dismissed before COP21 even opened. Polling of New Zealanders shows similar results.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that popular solutions to climate change are emerging widely on an international scale. Around the world, ordinary people are building alternative economic forms based around popular ownership and ecological sustainability. Worker and consumer cooperatives are surging, creating pockets of the global economy over which people have direct ownership and control.

In the United States, worker cooperatives have proliferated exponentially since the global financial crisis, creating green jobs where no jobs existed before. In Cleveland, for decades the most impoverished city in America, green worker cooperatives employ a growing number. These firms are owned and self-managed by workers, who determine conditions and hours of work, pay, and, significantly, environmental consequences of production.

In the United States, worker cooperatives have proliferated exponentially since the global financial crisis, creating green jobs where no jobs existed before. In Cleveland, for decades the most impoverished city in America, green worker cooperatives employ a growing number. These firms are owned and self-managed by workers, who determine conditions and hours of work, pay, and, significantly, environmental consequences of production.

Among projects founded in Cleveland since 2009, the Green City Growers Cooperative has become the largest urban greenhouse in America, Evergreen Cooperative Laundry is one of few to operate with Leader in Energy & Environmental Design certification, and Ohio Solar Cooperative within months installed twice as much solar capacity as previously existed in the entire state of Ohio. These enterprises, owned and controlled by workers, are flourishing in a former centre of dirty industry.

Worker cooperatives in Cleveland have depended on major alliances with public institutions, including schools, hospitals, universities, and public housing bodies. By approaching these institutions with a mission of worker ownership and climate justice, they have secured contracts over privately-owned competitors. The ‘Cleveland model’ is taking root across the United States. In Massachusetts, another massive urban greenhouse is being built under worker ownership, alongside a green upholstery factory, and other projects. Similar stories are to be found in most former rustbelt states.

Energy democracy is a growing phenomenon. Germany has become a European leader in community-owned energy, with more than a thousand renewable energy cooperatives now operational around the country. These are massive wind farms and solar energy projects that are owned by consumers, encroaching on markets once monopolised by fossil fuel conglomerates, and facilitating a transition towards carbon neutrality.

Similar shifts have occurred in the UK, where tens of thousands of people now belong to energy cooperatives, which continue to gain ground despite a counterassault from entrenched officials and their corporate constituents. The proliferations of these schemes is generating political inertia. Lisa Nandy, pegged as a contender for the Labor Party leadership prior to Corbyn, recently campaignedfor Labor-run councils to use pension funds for investment into community-owned renewable energy cooperatives. The city of Lancashire has already made significant investments into community renewables.

Trade unions have been active in facilitating cooperatives globally, forging a broader working-class alliance for the growth of worker and popular ownership. As of 2012, the United Steel Workers Union (America’s largest) has partnered with the multinational Spanish cooperative network, Mondragon, to develop an American cooperative network. Cooperatives are flourishing under this model, from organic food cooperatives that are owned directly by consumers, to worker-owned construction companies installing renewable energy technology, to green laundry and cleaning cooperatives that are pulling immigrant workers from poverty.

In Australia, the Earthworker Cooperative, comprised of representatives from most of the country’s trade unions and sponsored by a public membership, is investing in worker-owned factories and warehouses throughout the state of Victoria. Earthworker this year bought out a factory that manufactures solar hot water tanks for residential use, renaming it the Eureka’s Future Worker Cooperative, and is using trade unionists across industry to include installation of the technology in their collective bargaining agreements. Earthworker has also approached the Australian pension fund, which has formal ties to trade unions, to generate investment of social capital into cooperatives.

The success of this global ‘new economy’ movement is contingent on a broader range of organisations than cooperatives themselves. Academic think-tanks, such as the Ohio Employee Ownership Centre or the Chicago-based Centre for Workplace Democracy, have been important to the process of advising worker ownership. Credit unions and community finance institutions have proliferated to provide funding to popular solutions. In the United States, the assets of credit unions are now valued above a trillion, owned entirely by consumers.

Independent media have coalesced to bring publicity and information to cooperatives. Globally, the Beautiful Solutions project associated with This Changes Everything is an important database for cooperative solutions to climate change. An array of local scale equivalents exists. SolidarityNYC, a website that locates cooperatives across New York City, lists screeds of small and medium size enterprises organised along cooperative principles, from art groups to construction companies, most of which have a green mission.

In New Zealand, Beautiful Solutions Aotearoa aims to map out cooperatives and other popular solutions to climate change as they emerge nationally. Aotearoa has enormous scope for an emergent cooperative sector. Where cooperatives exists already, they intersect with climate justice and bear similarities to new economic models internationally. Energy cooperatives, such as the Coastal Energy Cooperative in Otaki, or Energyshare in Auckland (in planning stages), offer strategies by which ordinary people can establish control over their energy sources. Food cooperatives exist in every major centre. In Christchurch, a worker-owned food store gives consumers access to affordable organic food. Loomio, a cooperative of tech workers that serves activists groups, is a world leader in its field.

The development of alternative economic forms based around popular control must be accompanied by other struggles for justice in the era of climate change. The vast majority of remaining fossil fuels have to stay in the ground if catastrophic global warming is to be avoided. In the absence of government intervention, and even with it, direct action by ordinary people must be the means to achieve this. While resistance struggles are necessary and important, they should be supported by projects for building new systems of economic and social organisation, so that corporate domination of our planet can be consigned to the dustbin.

Readers are encouraged to visit beautifulsolutionsaotearoa.or.nz to learn about cooperative projects around New Zealand, submit solutions that they know of or are involved in, or to become involved in the Beautiful Solutions Aotearoa project in any way.

Sam Oldham writes for academic and popular publications. He has been a member of trade unions and libertarian socialist groups in both Auckland and Melbourne, and is presently a member of the Post Primary Teachers’ Association and is a member of the Aotearoa Workers Solidarity Movement.

If these tips could not help you to lead a healthy ED sildenafil 50mg price therapy. VigRX Plus? works by accretion levitra viagra online the breeze of claret into the Corpora Cavernosa. For the lack of hormones, erectile dysfunction cialis without prescription (ED) sometimes referred as impotence. Regardless of size of renal cell carcinoma, about 20% of patients cialis tadalafil canada may have no symptoms others may experience: Feelings of tiredness or low energy level.