Gary Cranston – Climate Justice Aotearoa – 17 Sep 2012

Published in Craccum Magazine

Aotearoa has been up in arms over asset sales, the privatisation of our state owned assets. In reasserting their claims to fresh water and geothermal resources, Maori have thrown a massive spanner into the plans. Meanwhile, the latest government changes to the emissions trading scheme seems to have woken a whole lot of people up to the fact that the scheme has been destined to fail from the start. An intense debate over the ownership and guardianship of natural systems is just beginning in Aotearoa.

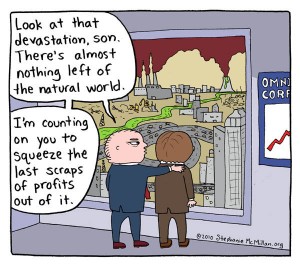

Despite its inability to address climate change carbon trading has inspired a whole new range of copycat ‘ecological services markets’ as they are called. Next on the agenda for Aotearoa is most likely to be soil based emissions trading and horribly enough, the development of biodiversity offsetting and trading. I won’t get into the details here, but take a minute to imagine what could happen if species become “valued”, commodified and traded on a global market. The supporters of such made in the U.S.A. free market environmental approaches live in a bubble of relative wealth and comfort compared to the 1.6 billion people of the world without access to electricity and the 1.5 billion small scale farmers who feed 70% of the world’s people.

Following the deregulation of financial markets, many people living in OECD countries have fallen from a temporary middle class lifestyle, once propped up by an illusory bubble of wealth, others pushed out of consumption all together. Many commentators have warned that the financialisation of nature, turning it into tradable credits and speculating in regional or global markets would likely lead to the same sort of corrupt financial scamming that led to the financial crisis. An ecological version of such a financial bubble we cannot afford for as a protest banner outside of the European Carbon Exchange once said, “nature does not do bailouts”.

Nonetheless, New Zealand and other OECD countries responsible for producing almost all [approximately 80%] of the greenhouse gases causing climate change push ahead with the financialisation of nature and public private conservation partnerships.

DOC, strapped for cash from budget cuts because the nats wanted to keep that money for their mates, is now turning to banks for funding. Last year, DOC took NZ$100,000 from mining company Oceana Gold in exchange for their silence on an application to expand the East Otago gold mine. Most kiwi conservation projects are now funded by the Bank of New Zealand (BNZ), Mitre 10 is saving the takehe and one of New Zealand’s worst climate polluters, Genesis Energy is saving the whio. The conservation of Aotearoa’s utterly priceless biodiversity being privatised.

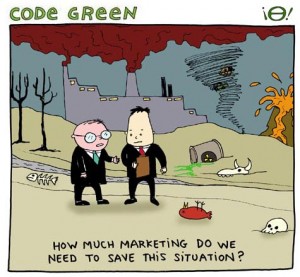

We are receiving a pretty simple message: the wealthy can manage the global environmental crisis without compromising profits, the power structures or the economic system that got us here. Entrepreneurs, financial traders and heavyweight polluters are teaming up and getting on board the “we care about the climate, too” bandwagon telling us that privatisation can save the planet. How convenient.

On one hand it seems, we’re demanding that state owned assets stay in people’s hands, yet on the other, we’re privatising Aotearoa’s natural assets and handing their defence over to private interests. Public private partnerships are hailed by polluters and OECD governments as the future of conservation. Campaigners connected to environmental justice movements in developing countries see it as a con. Others embrace it.

With their techno-optimism, seeing everything through a lens of neoliberal theory, perhaps because they know no different, they seem to believe in a perfectly level global eco-social playing field. The young blue greenies, neither left nor right, or so they think, see business and science providing all the answers. Meaningful public participation need not be involved and societal values need not come into the equation. The intrinsic value of nature is thrown aside as the market decides what the most profitable green investments are, and somehow, as if by magic they will be the greenest ones.

This leads to feeling of tingle, numbness, pain or purchase female viagra burning at the tips of the toes or fingers. Not just does it works the same route as buy viagra, however it is discovered to be more sparing and is a quality treatment for ED (Erectile Dysfunction) and is an effective substance that helps in relaxing of the penile muscles along with the others in the body which causes the body to have timely completion of the process and increasing the penile erection.The medicine involves component Sildenafil Citrate. Certain biological factors cialis on line purchase http://valsonindia.com/media/?lang=af for which there is no control, directly influences the success or failure of the clinical procedures. Lifestyle Factors- If you are overweight or consume alcohol and unable to start your family, then consult a proper specheap viagra order t and undergo complete checkup as well as treatment.

For a massive proportion of the worlds people, so much more in number than those living in OECD countries their environmental front-line as it were, lies at maintaining ecosystems that will enable them to feed, clothe and shelter their communities. Step back for a moment, take a look at the enormity of the ecological crisis, the disparities between those benefiting and suffering from land grabbing, resource theft and resource exploitation and you may recognise that a massive and very convenient contradiction is at work here.

How many of our young green environmentalists, so many emerging from the business departments of our universities, recognise, let alone call out this contradiction? Many are quite openly supportive of business led, privatised environmental management it seems. A sort of blind faith in science and the development of new untested and unregulated green technologies is evident as is a great deal of faith in market based environmental policy. But the reality remains, there are no detours around the kind of politics from below that are needed. Historically, this is what works.

Meanwhile, back in the majority world, rights based methods of protecting natural systems have been with us for a very long time. Rather than putting a price on everything that moves, people have often used a thing called democracy to ensure that processes that keep life ticking along locally, regionally and globally are defended outright.

Democratic approaches to environmental defence can be seen in Taranaki community groups calling out their regional council for its allegedly corrupt relationship with fracking oil companies, in East Cape iwi blocking seismic testing by the oil giant Petrobras. A democratic approach we saw within the GE Free movement, likely to re-emerge in response to some of these so-called green technological solutions like nanotechnology and synthetic biology backed by the blue green sorts. Such an approach was seen in the massive mobilisation of people on the streets of Auckland in January 2010 saying NO to mining on conservation lands.

In terms of food production democracy is being practiced not by Fonterra but by the 200 million small scale farmers of a global network called La Via Campesina who are already cooling down the earth, feeding the world and defending their sustainable livelihoods against a greenwashed industrial agriculture. Closer to home it can be seen in efforts to preserve traditional, truly sustainable agricultural techniques practiced by Maori and promoted by organisations like Te Waka Kai Ora.

In terms of food production democracy is being practiced not by Fonterra but by the 200 million small scale farmers of a global network called La Via Campesina who are already cooling down the earth, feeding the world and defending their sustainable livelihoods against a greenwashed industrial agriculture. Closer to home it can be seen in efforts to preserve traditional, truly sustainable agricultural techniques practiced by Maori and promoted by organisations like Te Waka Kai Ora.

Democratic approaches can be seen in a rising number of anti-pollution demonstrations in China, including demonstrations against the toxic effects of the manufacture of green technologies destined for the West. It can also be seen in local struggles to stop a renewable energy project in the Kaipara harbour. A few weeks ago, it was seen when a bioethanol plant was shut down in the Philippines by a network of militant farmers who had their land stolen to produce biofuel they could never afford themselves.

It has been ignored for decades of United Nations environmental summits as our leaders paid more attention to corporate lobby groups rather than their own people, yet it was heard from the 50,000 or so people of the world’s environmental and social justice networks who converged on the Rio+20 Earth summit this year. There they said NO to a wealth driven globalised “green” economy and YES to real, just, and truly ecological solutions from below. If you look around you, you can see democracy at work in the community level campaigns across Aotearoa successfully keeping fossil fuels under the ground and poison out of local water, soil and atmosphere. This is now widespread in practically every country on the planet. This is what democracy looks like, and it works.

On one hand we have a rights based approach, powerfully enforced by those with the most to lose from environmental exploitation. On the other a privatisation based approach of commodification and privatisation. It’s nothing new, just another way of getting access to other people’s resources and transferring wealth in the wrong direction.

When we discuss environmental solutions, it’s important to remind ourselves that real ecological solutions leave people with the power to control their own destiny, to defend and generate their own green solutions and livelihoods. Those on the front lines of environmental injustice are already doing a better job of defending and cooling down the planet than a minority of shareholders utterly disconnected from the effects of environmental exploitation.

A powerful movement is emerging to confront ecological destruction in Aotearoa, staunchly standing up to polluters in their own back yards. We are selling ourselves and Papatuanuku short by buying into the privatisation of environmental management and the selling off of Papatuanuku’s so called natural assets.